By Wayne Heming

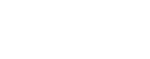

Anyone who played with or against Gavin “Jed” Allen will tell you he played mostly on heart.

So it was ironic that 14 years after helping an underdog Queensland to State of Origin’s greatest upset in 1995, Allen’s big heart had to be replaced in a life-saving transplant operation.

A raw, dry, rangy, shy kid from Cairns in north Queensland Allen picked up the nicknamed Jed when he joined Valleys in the late 1980s.

Several members of the Valleys team, including Allen, would sit in the old club bar watching the TV series Beverly Hillbillies featuring Jed Clampet, and the name just stuck.

Allen built a FIERCE reputation in rugby league as a tough, no-nonsense prop forward in an era where the game exploded with tough front-rowers.

In Brisbane’s first grand final win in 1992 against his former club, St George, Allen set up an early try for halfback Allan Langer which set the Broncos on the path to glory.

But it was his tireless work rate in a pack that included Glenn Lazarus, Trevor Gillmeister, Kerrod Walter, Alan Cann, and Terry Matterson, that stood out in the club’s 28-8 maiden premiership win.

Come 1995, Allen’s career was winding down.

Brisbane coach Wayne Bennett had stocked up on front-rowers at the club with Lazarus, Andrew Gee, and Mark Hohn making it tough for Allen to get a start.

When Super League emerged on the scene in 1995, Allen was offered a contract by rebel league organiser, John Ribot, but turned it down.

He was the only Bronco player not to grab the big dollars being thrown around.

In some ways, It turned out to be a blessing for Allen who ended his career as a Maroon hero.

FOGS great Paul Vautin to this day says Allen’s role in the ’95 whitewash of the Blues was never fully recognised.

“There was myself, Arthur Beetson, Les Geeves, and the late Ross Livermore in a meeting when “Cracker” (the late QRL Chairman John McDonald) walked in and told us emphatically that no Super League players were to be picked,” said Vautin, the mastermind, and motivator behind the stunning 3-0 series ambush.

“We were really struggling for players because we couldn’t pick any players aligned with Super League,”

“When we found out Jed, (Allen) was available because he was the only Bronco player who didn’t sign with Super League he was a “gimme” selection.

Vautin said Allen’s role through the entire series was “very understated”.

“He did so much behind the scenes with other forwards.

“He didn’t say a lot, he didn’t have to.

Vautin said when the team got together for its final training run at Lang Park before flying to Sydney for the opening game of the series, he broke the team into groups between the backs, halves, and forwards.

“I told the groups I wanted them to chat to each other about how they were feeling and about the game,” recalled Vautin.

“I walked over to Jed’s group, which included Mark Hohn and Tony Hearn, who were sitting on the grass and Jed stood up and said to me: ‘We’ve been talking and we have a question I need to ask you’.”

“I said: ‘What is it, go on, fire up’”

“Jed then said to me: ‘Are we allowed to fight?

“My response was simple.

“Jed it’s Origin mate, anything can happen and you certainly have my permission to do whatever it takes and if that involves putting one on someone’s chin, by all means, do it, but once the fighting is over, get back and play your footy.’

Allen puts the ’95 Origin series at the top of his career highlight list.

Surprisingly there were no fisticuffs in the Sydney Origin.

But all hell broke loose in the return game in Melbourne with 26 players involved in a wild brawl lasting several minutes which spilled across the MCG field.

Vautin said he’d been tipped off that the first Maroons player to utter the famous “Queenslander” call in Sydney, would be bashed by the Blues.

“I got a phone call the day of the match from some in Sydney telling me the Blues would bash the first player to call out Queenslander which was our call to arms.

“I told the players at our pre-game meeting about it and I asked them: ‘So who’s going to yell it out?’

“Seventeen hands went straight up. Even our reserves put their hands up and I think even the great Tosser (legendary team manager Dick Turner), might have put his hand up as well.”

“It generated an amazingly positive feeling amongst the players as they ran onto the field that night.

“Jed didn’t start it, but he certainly finished it.

“He wasn’t a fighter, but he was so tough and he just got the job done whoever he played against.

‘He was stoic, silent but incredibly generous with his time and a lovely guy.

“He went on after that to be one of the great managers of the Queensland team.

Some 14 years after playing the last of his eight games for Queensland, Allen underwent a life-saving heart transplant at Brisbane’s Prince Charles Hospital.

With his condition rapidly deteriorating in 2018 he was quickly running out of time.

“It was either get a suitable heart donor, or die,” Allen, now almost five years on from his life-saving surgery told FOGS.

“My Dad had a heart condition years earlier and ended up having a heart transplant.

“He was the 13th person in Queensland to undergo a heart transplant.

“When I went to the hospital and told the doctors about my family history, they wouldn’t let me leave.

“I spent a week in hospital undergoing a battery of tests before doctors broke the news to me that I was battling a genetic heart condition.

Allen gave up alcohol, changed his diet, and undertook a regular exercise routine.

With new medication, which included what he called a “wonder drug and later an electric pump implanted in his chest, he was able to keep going until crunch time arrived.

Picture this scenario.

Your health is going downhill rapidly to the point where you can barely breathe or walk 10 paces.

You are told you are on the waiting list for a replacement heart and that if one becomes available, it has to not only be compatible but also has to fit your body shape.

Then you are told: “But it could take another 12 months to find one.”

Allen underwent his heart transplant in December 2018 but doesn’t know the identity of the donor who saved his life.

He was not given that information and the family of the donour was not told Allen was the recipient.

He was allowed to write a letter to the family which the Prince Charles passed on.

“It took me a year to write it because I couldn’t find the words to properly express my feelings straight away,” he said.

Allen’s wife, Christine was always by his side while running the house and looking after his four children, Luke, Joshua, Kaitlyn, and the youngest, Jake.

“It did put a strain on our relationship because I was always ill and it’s hard to be happy when you are not feeling well.

Allen said he never wanted people to feel sorry for him because he was given a second chance at life.

But he did have a message for others to consider.